What it Means to Watch Dune Today

Dune is clear about its stance on colonizers. It's less clear about how it views the colonized.

At the very outset, Dune: Part Two is an immense, operatic triumph of filmmaking. It raises all the right questions about geopolitics, its sympathies are in the right place.

It is clearest about where it stands on White saviors. They’re dangerous. The more messianic they are, the worse the implications. It’s also clear about its stance on imperialism – both films and the books are hardly subtle about the desert planet’s analogy with the Middle East.

In Arrakis, the precious resource, spice, is the real world equivalent of oil. Imperialist powers – Atreidies and Harkonnen Houses being thinly veiled surrogates for USA and Soviet Russia – fight proxy wars on a foreign terrain to acquire control of the most important resource in the universe. What follows is subjugation of the population native to that land – the Fremens – a fact which Chani, one of the Fremens and Paul Atreidies’ subsequent lover, makes clear in the opening of the first film when she asks: “who will our next oppressors be?” It doesn’t matter whether imperialists are gentle or brutal in their hand, when both kinds ultimately take what isn’t theirs and disrespect the sovereignty of an entire people. For the time in which Herbert wrote the novels – at the height of the Cold War, when proxy wars between the two superpowers lay waste to several developing nations, including the Middle East – this made sense. What about now, when the biggest crisis in the Middle east right now is fought over identity and sovereignty?

Here’s where Dune starts to falter: does it give the Fremen enough agency to lay claim to that sovereignty?

Sovereignty isn’t just territory; it’s also self-determination. That requires one to know themselves and assert their identity. There isn’t a more pressing time to contend with this than right now; this makes it hard to ignore the shadow of Palestine looming over Dune. We’re watching it at a time when the International Court of Justice is hearing a case to determine whether Israel is committing genocide in Gaza. It’s been nearly five months since the assault on Gaza began, and tens of thousands of lives have been lost – all over an intractable question over sovereignty: can there ever be a free, sovereign Palestine? Unlike Arrakis, it’s not so much a resource question here, though economics is certainly part of the geopolitical alliances on the issue. It’s identity and agency. The philosopher Hannah Arendt famously said, “if one is attacked as a Jew, one must defend oneself as a Jew.” It cements the idea that embracing the identity for which one is persecuted is not only key to resisting oppression but erasing that identity would be anathema. Dune, however, wants to talk about the political economy of Western imperialism in the Middle East without sufficiently engaging with its identity and, by extension, religion. Religion is treated as a tool for political maneuvering, rather than as a core part of Arabic culture.

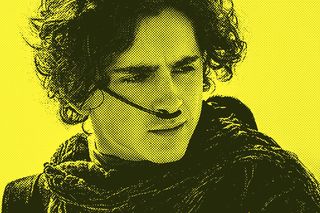

Take the fact that religious beliefs in the film are painted as irrational and, more troublingly, are played for laughs. Javier Bardem’s Stilgar, for instance, is reverential to Timothee Chalamet’s Paul to the point of obsequience, as are the rest of the “Southerners” on Arrakis, who hypnotically repeat “Lisan-al-Ghaib” like an incantation in the face of any feat of strength they witness from Paul. Though Chani is openly critical of this tendency and sees through the machinations of imperialist powers leveraging religion against the Fremen, it doesn’t ultimately prevent the bleak conclusion: the Fremen turning into a willing army about to carry out a genocidal “holy war” at the behest of a White savior who wants to plunder the planet without any opposition, like any other imperialist conqueror. Almost without a will – or agenda – of their own.

This also paints faith – which, in anti-colonial struggles, is often an important guiding philosophy – as a lie planted by colonizers, rather than a philosophical treatise in its own right, with its own influential cosmology. The books understand this and accordingly pepper the entire world-building with Islamic references as a means to show that Islam is an inextricable part of world history, subject to undergo changes – not erasure – even millennia into the future. In the films, we only see the prophecy of the “Lisan-al-Ghaib” as being planted among the Fremen by the shadow government, the Bene Gesserit, who are a group of powerful women, capable of manipulating blood-lines, political alliances, and religious beliefs in accordance with their own designs. Centuries before the events of the two films take place, they placed the idea of a messiah in the oppressed Fremen people, who latch on to it and wait for his arrival – from the outside, despite their stated distrust of outsiders. In the film, the Fremen receive Paul with a little suspicion at first, followed by unquestioning, rapturous devotion to his cause, even when it takes them further away from their own. The idea of jihad, so central to the books as resistance to imperialist oppression, is then distorted into the very stereotype that perhaps made the use of the term “jihad” in the movies an unspoken no-go: the “holy war” is seamlessly co-opted as terrorism.

The Gender Politics of ‘Dune’ Keep It From Being Truly Ahead of Its Time

“Herbert’s nuanced understanding of jihad shows in his narrative. He did not aim to present jihad as simply a ‘bad’ or ‘good’ thing. Instead, he uses it to show how the messianic impulse, together with the apocalyptic violence that sometimes accompanies it, changes the world in uncontrollable and unpredictable ways,” noted Ali Karjoo-Ravary. This is true of the Dune films to a certain extent. But once again, it’s difficult to evaluate its approach to the idea sans real-world events. Palestine is often framed in Western media as a belligerent threat to peace in Israel as the “only democracy” in the Middle East; Israel’s current attack on Gaza is thus framed as legitimate self-defense. The trope of the easily pliable, dangerous Arab carrying out large-scale violence is one that has played out with real consequences in real life: on screen, this real-world context just dilutes the film’s intended messaging to critique how imperialism works.

In focusing so much on showing us the folly of White saviorism, then, Dune (the film) forgets to account for the agency – or even the identity – of the Fremen, who end up, against the film’s wishes, as the “other.” “Seeking to save Muslim and MENA peoples from taking offense, Villeneuve — as Paul does to the Fremen — colonizes and appropriates their experiences. He becomes the White savior of ‘Dune,’” writes Haris A. Durrani.

There has justifiably also been a lot of criticism of Dune’s confused position on Arabs: does it appreciate or appropriate Arabic culture, and more generally, Islam? The Fremen are Bedouin-coded, but in the films are cast as a generic group of Black and Brown “other” – revealing the film’s own lack of attention to the side it seems to speak on behalf of. And so it raises the question: who is the White savior critique meant for, considering the White director and White-majority cast participate in a story that centers the very Whiteness it wants to critique? “The hard questions of how we can admire ‘Dune’ on screen when there are no Arabs in its Arab images cannot be ignored. Without Arabs, the movie’s Arab-ness becomes just another stolen resource to enrich the European-coded noble houses,” Khaldoun Khelil observes.

Still, Dune is a deeply thoughtful, introspective meditation on White supremacy and its catastrophic exploits. It successfully captures the essence of Western civilization: one that is built upon plunder and genocide. In the documentary Exterminate All the Brutes, Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck shows how, for centuries, European powers have justified the slaughter of indigenous populations in order to appropriate their resources by characterizing them as the violent, unstable “other.” Terrifying visions of this civilizational anxiety appear in Dune when the Harkonnen steward Rabban, frustrated at his inability to gain control of spice production on Arrakis, screams at his henchmen to kill all the “rats,” referring to the Fremen. The genteel, benevolent demeanor of the Atreidies isn’t less suspect either: Lady Jessica, the Bene Gesserit mother of Paul Atreidies, views the Fremen as pliable and meek when she plots to install Paul as their messianic leader. To her, they are just another resource to manipulate, rather than ally with as equals.

Dune’s commitment to critiquing empire is timely and subversive – especially in a world where the going narrative strongly reinforces the logic of conquest in the Middle East. Its issues with representation go all the way back to Herbert’s books, which raises questions as to how adaptations can remain faithful to the core of their source materials when the latter themselves are laden with problems. However, the ongoing loss of Palestinian lives in the backdrop of this film’s release makes it hard to engage with its themes without reflecting on what it means for the world at large – given that it owes so much of its existence to Arabs and Arabic culture. If there can be no Dune without the Middle East, can we afford to separate it from what’s going on in the Middle East right now?

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Is This Normal? 'I Avoid Making Decisions Because It's Too Overwhelming'